Poetry

Synopsis:

A picture of the Riel Resistance from one of Canada’s preeminent Métis poets.

With a title derived from John A. Macdonald’s moniker for the Métis, The Pemmican Eaters explores Marilyn Dumont’s sense of history as the dynamic present. Combining free verse and metered poems, her latest collection aims to recreate a palpable sense of the Riel Resistance period and evoke the geographical, linguistic/cultural, and political situation of Batoche during this time through the eyes of those who experienced the battles, as well as through the eyes of Gabriel and Madeleine Dumont and Louis Riel.

Included in this collection are poems about the bison, seed beadwork, and the Red River Cart, and some poems employ elements of the Michif language, which, along with French and Cree, was spoken by Dumont’s ancestors. In Dumont’s The Pemmican Eaters, a multiplicity of identities is a strengthening rather than a weakening or diluting force in culture.

Awards

- Winner of the 2016 Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry

Reviews

“A rollicking poem about the fiddle ('the first high call of the fiddle bids us dance/baits with its first pluck and saw of the bow/reels us, feet flick — fins to its lure and line') becomes a statement of cultural pride and defiance — much like The Pemmican Eaters as a whole.” — Toronto Star

“Dumont’s work is visual and evocative, highlighting recurring symbols and images of a natural world that will be familiar to any dweller of the Prairies . . . The Pemmican Eaters builds off the poet’s earlier work and highlights a writer who has mastered both craft and voice.” — Quill & Quire

“Dumont honours Métis traditions in music and beadwork in a number of lyrically driven poems. The Pemmican Eaters is a statement of cultural pride and defiance, much like Marilyn herself.” — CBC News Online

“Marilyn Dumont uses both rhythmic and free verse to provide a brilliant and insightful look at Métis and Cree people.” — Scene Magazine

Educator Information

This book would be useful for grades 9 - 12 in courses such as creative writing, English language arts, and social studies. Also recommended for students a college/university level.

Additional Information

96 pages | 5.50" x 8.50"

Synopsis:

The poetry of Clay Pots and Bones is Lindsay Marshall’s way of telling stories, of speaking with others about what things that matter to him. His heritage. His people. His life as a Mi’kmaw. For the reader, Clay Pots and Bones is a colourful journey from early days, when the People of the Dawn understood, interacted with and roamed the land freely, to the turbulent present and the uncertain future where Marshall envisions a rebirth of the Mi’kmaq. The poetry challenges and enlightens. It will, most certainly, entertain.

Additional Information

96 pages | 5.00" x 8.00"

Synopsis:

In the North Arm of British Columbia’s Fraser River lies an uninhabited island. In the midst of major industry and shipping, it is central to the waterfront of British Columbia’s original capital of New Westminster passed by daily by thousands of SkyTrain commuters. Poplar Island is lush and unspoken, but storied. It is the traditional territory of the Qayqayt First Nation. Made into property, a parcel of land belonging to the “New Westminster and Brownsville Indians,” this is the location of one of British Columbia’s first “Indian Reserves.”

This is also a place where Indigenous smallpox victims from the south coast were forced into quarantine, substandard care and buried. As people were decimated the land was taken and exchanged between levels of government. The trees were clear-cut for industry, beginning with shipbuilding during the First World War. The island still serves as booming anchorage for local sawmills.

From the Poplars is the poetic outcome of archival research, and of listening to the land and the stories of a place. It is a meditation on an unmarked, twenty-seven and a half acres of land held as government property: a monument to colonial plunder on the waterfront of a city, like many cities, built upon erasures. From an emplaced poet and resident of New Westminster, this text contributes to present narratives on decolonization. It is an honouring of river and riparian density, and a witness to resilience, tempering a silence that inevitably will be heard.

Synopsis:

In Halfling Spring , a series of notes unfolds the dance of desire versus trust through a long season of actual and metaphorical springtime.

Joanne Arnott is a Métis/mixed blood mother of six, and in this collection she continues her explorations of love, intimacy, and family, with a focus on electronic connections (internet love). Transiting Canada from Victoria to Iqaluit, and transitioning from virtual to real (fantasy to reality), she inspects the realms of miscegenation and love in a class conscious and cross-cultural context, revealing en route the many ways that our deepest connections unveil the depths of old pain.

Optimistic and playful, romantic and mythic, affirming embodiment, this process of poetic revelation shows all the dirty tricks of love.

Synopsis:

George Kenny is an Anishinaabe poet and playwright who learned traditional ways from his parents before being sent to residential school in 1958. When Kenny published his first book, 1977’s Indians Don’t Cry, he joined the ranks of Indigenous writers such as Maria Campbell, Basil Johnston, and Rita Joe whose work melded art and political action. Hailed as a landmark in the history of Indigenous literature in Canada, this new edition is expected to inspire a new generation of Anishinaabe writers with poems and stories that depict the challenges of Indigenous people confronting and finding ways to live within urban settler society.

Educator & Series Information

Indians Don’t Cry: Gaawin Mawisiiwag Anishinaabeg is the second book in the First Voices, First Texts series, which publishes lost or underappreciated texts by Indigenous artists. This new bilingual edition includes a translation of Kenny’s poems and stories into Anishinaabemowin by Patricia M. Ningewance and an afterword by literary scholar Renate Eigenbrod.

Although most of the books in this series are non-fiction, this one is listed as fiction.

Additional Information

190 pages | 5.50" x 8.50"

Synopsis:

Mohawk spoken-word artist Janet Marie Rogers's newest collection pulses with the rhythms of the drum and the beat of the heart. Poems drawing on the language of the earth and inflected with the outspoken vocality of activism address the crises of modern "land wars"-environmental destruction, territorial disputes, and resource depletion.

Synopsis:

The New Wascana Anthology is named for the Cree word "oskana," meaning "bones,"* but this anthology is no literary graveyard. It will introduce you to stories, poems, and essays that can be discussed over drinks, or used to impress friends years after leaving English 100 behind.

Offering a taster's choice of the best Canadian writing, with a special focus on Aboriginal and Prairie writers, this anthology includes pieces selected to introduce you to the English literary canon. Going back hundreds of years, the oldest poems included here have no known author, while the youngest writer is a recent university graduate.

Building on the bones of the canon (including all of Canada's Man Booker Prize-winners and newest Nobel Laureate), The New Wascana Anthology features writers such as Flannery O'Connor, Thomas King, Carmine Starnino, and Ursula K. Le Guin who will challenge your worldview. Most importantly, this anthology is about turning the page, opening your mind, and revelling in the pleasures of reading.

*The bones referred to are the bones of plains bison, a species that once numbered in the tens of millions on the Great Plains.

Educator Information

Contains works from Indigenous and non-Indigenous writers.

Table of Contents

Preface

Poetry

Anonymous

Summer is icumen in

Sir Patrick Spens

Mary Hamilton

Geoffrey Chaucer (ca. 1343–1400)

from The Canterbury Tales

Excerpts from General Prologue

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503–1542)

The Long Love, That in My Thought Doth Harbour

Sir Walter Ralegh (ca. 1552–1618)

The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd

Edmund Spenser (ca. 1552–1599)

from Amoretti

30. My love is like to ice

75. One day I wrote her name

Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586)

from Astrophel and Stella

59. Dear, why make you more of a dog than me?

Michael Drayton (1563–1631)

from Idea

61. Since there’s no help, come let us kiss and part

Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593)

The Passionate Shepherd to His Love

William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

from Sonnets

18. Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

20. A woman’s face, with nature’s own hand painted

116. Let me not to the marriage of true minds

130. My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun

from As You Like It

All the world’s a stage

John Donne (1572–1631)

A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning

Death be not proud

The Bait

The Flea

Ben Jonson (1572–1637)

Epigram XXII: On My First Daughter

Epigram XLV: On My First Son

Song: To Celia

George Herbert (1593–1633)

Love (III)

John Milton (1608–1674)

When I Consider How My Light Is Spent

from Paradise Lost, Book 1

The Invocation

Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672)

Before the Birth of One of Her Children

The Author to Her Book

Andrew Marvell (1621–1678)

To His Coy Mistress

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchelsea (1661–1720)

To the Nightingale

A Letter to Daphnis, April 2, 1685

Alexander Pope (1688–1744)

The Rape of the Lock

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762)

Addressed to—

Thomas Gray (1716–1771)

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

Christopher Smart (1722–1771)

from Jubilate Agno

My Cat Jeoffry

William Blake (1757–1827)

from Songs of Innocence

The Chimney Sweeper

The Lamb

from Songs of Experience

A Poison Tree

London

The Chimney Sweeper

William Wordsworth (1770–1850)

A slumber did my spirit seal

Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802

I wandered lonely as a cloud

The world is too much with us

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

Kubla Khan

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788–1824)

She Walks in Beauty

The Destruction of Sennacherib

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)

Ozymandias

John Keats (1795–1821)

La Belle Dame Sans Merci

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

Ulysses

Robert Browning (1812–1889)

Porphyria’s Lover

My Last Duchess

Emily Brontë (1818–1848)

Remembrance

Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d

Matthew Arnold (1822–1888)

Dover Beach

George Meredith (1828–1909)

from Modern Love

17. At dinner, she is hostess, I am host

Emily Dickinson (1830–1866)

F479. Because I could not stop for Death

F591. I heard a Fly buzz—when I died

F620. Much Madness is divinest Sense

F1096. A narrow Fellow in the Grass

F1263. Tell all the Truth but tell it slant

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Jabberwocky

Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)

The Ruined Maid

The Convergence of the Twain

The Workbox

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889)

God’s Grandeur

Pied Beauty

The Windhover

A. E. Housman (1859–1936)

from A Shropshire Lad

XIX. To An Athlete Dying Young

Sir Charles G. D. Roberts (1860–1943)

Tantramar Revisited

Archibald Lampman (1861–1899)

Heat

William Butler Yeats (1865–1939)

The Second Coming

Leda and the Swan

Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop

Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869–1935)

Miniver Cheevy

Robert Frost (1874–1963)

After Apple-Picking

Mending Wall

Nothing Gold Can Stay

The Silken Tent

William Carlos Williams (1883–1963)

The Red Wheelbarrow

This is Just to Say

Pictures from Brueghel

D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930)

Piano

Snake

Ezra Pound (1885–1972)

In a Station of the Metro

The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter

Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

Break of Day in the Trenches

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950)

Elegy before Death

What lips my lips have kissed

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Dulce et Decorum Est

e.e. cummings (1894–1963)

“next to of course god america i

anyone lived in a pretty how town

F. R. Scott (1899–1985)

Lakeshore

Langston Hughes (1902–1967)

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

Harlem

A. J. M. Smith (1902–1980)

The Lonely Land

Far West

Stevie Smith (1902–1971)

Not Waving but Drowning

Earle Birney (1904–1995)

Anglo-Saxon Street

W. H. Auden (1907–1973)

Musée des Beaux-Arts

Theodore Roethke (1908–1963)

My Papa’s Waltz

A. M. Klein (1909–1972)

Heirloom

The Rocking Chair

Dorothy Livesay (1909–1996)

Green Rain

Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979)

In the Waiting Room

Irving Layton (1912–2006)

The Birth of Tragedy

Dylan Thomas (1914–1953)

Fern Hill

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

P. K. Page (1916–2010)

After Rain

Planet Earth

Robert Lowell (1917–1977)

For the Union Dead

Miriam Waddington (1917–2004)

Advice to the Young

Raymond Souster (1921–2012)

The Lilac Poem

Elizabeth Brewster (1922–2012)

The Night Grandma Died

Eli Mandel (1922–1992)

Houdini

Anne Szumigalski (1926–1999)

It Wasn’t a Major Operation

Don Coles (b. 1927)

Collecting Pictures

Robert Kroetsch (1927–2011)

Meditation on Tom Thomson

Rita Joe (1932–2007)

Axe Handles for Sale

I Lost My Talk

Sylvia Plath (1932–1963)

Daddy

Alden Nowlan (1933–1983)

The Bull Moose

Leonard Cohen (b. 1934)

A Kite Is a Victim

Suzanne

Robert Currie (b. 1937)

Young Boy, Fleeing

Glen Sorestad (b. 1937)

Ten Years

Now That I’m Up

John Newlove (1938–2003)

The Double-Headed Snake

Margaret Atwood (b. 1939)

Backdrop Addresses Cowboy

The Nature of Gothic

This Is a Photograph of Me

Seamus Heaney (1939–2013)

Bog Queen

Digging

The Names of the Hare

Patrick Lane (b. 1939)

Mountain Oysters

Gary Hyland (1940–2011)

from Arguments in the Garden of Prayer

1. So many frogs

14. The first sounds

Beth Brant (b. 1941)

for all my Grandmothers

Robert Hass (b. 1941)

Consciousness

Gwendolyn MacEwen (1941–1987)

Manzini: Escape Artist

Marie Annharte Baker (b. 1942)

Pretty Tough Skin Woman

Louise Glück (b. 1943)

Illuminations

Michael Ondaatje (b. 1943)

The Cinnamon Peeler

White Dwarfs

Dennis Cooley (b. 1944)

how there in the plaid light she played with his affections plied them spikes from his heart she stood by pliers in hand he has his pride

Craig Raine (b. 1944)

A Martian Sends a Postcard Home

Tom Wayman (b. 1945)

Did I Miss Anything?

Linda Hogan (b. 1947)

Cities Behind Glass

Lorna Crozier (b. 1948)

The Dirty Thirties

Poem about Nothing

from The Sex Lives of Vegetables

Radishes

Lettuce

Cauliflower

Beth Cuthand (b. 1949)

Four Songs for the Fifth Generation

Kathleen Wall (b. 1950)

Morning Nocturne

Joy Harjo (b. 1951)

She Had Some Horses

Gerald Hill (b. 1951)

Becoming and Going: An Oldsmobile Story

Di Brandt (b. 1952)

completely seduced

Louise Halfe (b. 1953)

She Told Me

Louise Erdrich (b. 1954)

Dear John Wayne

Indian Boarding School: The Runaways

Jacklight

Jeanette Lynes (b. 1956)

The Last Interview with Bettie Page

Anne Simpson (b. 1956)

Grammar Exercise

George Elliott Clarke (b. 1960)

Blank Sonnet

Michael Crummey (b. 1965)

Her Mark

Gregory Scofield (b. 1966)

His Flute, My Ears

Karen Solie (b. 1966)

Parasitology

Randy Lundy (b. 1967)

Bear

Ghost Dance

Stephanie Bolster (b. 1969)

To Dolly

Carmine Starnino (b. 1970)

Pepino’s Poem, “Growing Up in Naples”

Rope Husbandry

Daniel Scott Tysdal (b. 1978)

Metro

Cassidy McFadzean (b. 1989)

I smile earwide

Short Fiction

Sherman Alexie (b. 1966)

The Approximate Size of My Favourite Tumour

Margaret Atwood (b. 1939)

My Last Duchess

Sandra Birdsell (b. 1942)

Disappearances

Raymond Carver (1938–1988)

Cathedral

William Faulkner (1897–1962)

A Rose for Emily

Richard Ford (b. 1944)

Sweethearts

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935)

The Yellow Wall-paper

James Joyce (1882–1941)

Araby

Thomas King (b. 1943)

A Seat in the Garden

Ursula K. Le Guin (b. 1929)

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

Alexander MacLeod (b. 1972)

Miracle Mile

Alistair MacLeod (1936-2014)

The Boat

Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923)

The Garden-Party

Yann Martel (b. 1963)

The Facts Behind the Helsinki Roccamatios

Rohinton Mistry (b. 1952)

Swimming Lessons

Ken Mitchell (b. 1940)

The Great Electrical Revolution

Alice Munro (b. 1931)

The Bear Came over the Mountain

Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964)

A Good Man Is Hard to Find

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849)

The Cask of Amontillado

Eden Robinson (b. 1968)

Traplines

Gloria Sawai (1932–2011)

The Day I Sat with Jesus on the Sundeck and a Wind Came Up and Blew My Kimono Open and He Saw My Breasts

Guy Vanderhaeghe (b. 1951)

Dancing Bear

Dianne Warren (b. 1950)

Bone Garden

Critical Prose

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002)

Evolution as Fact and Theory

Trevor Herriot (b. 1958)

from Grass, Sky, Song: Promise and Peril in the World of Grassland Birds

A Way Home

Barbara Kingsolver (b. 1955)

Setting Free the Crabs

Don McKay (b. 1942)

Baler Twine: Thoughts on Ravens, Home, and Nature Poetry

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745)

A Modest Proposal

Copyright Notices

Index of Authors and Titles

Index of First Lines of Poetry

Additional Information

554 pages | 6.00" x 9.00" | Paperback

Synopsis:

A Night for the Lady explores the terrain of poetry conversation. Each poem arises from conversations with poets, colleagues and intimate friends. They range from a 1998 conversation on healing programs and the fundamentals of world change to a sequence of recent indigenous literary events on the prairies. Within the context of these conversations, an exploration emerges of the roles of woman within local as well as historic literary and global situations. The poems draw together diverse figures from world literature, world religions and myths to lay open the experience of human beings within the “brown-feminine.” Identifying and synthesizing connections across a wide palette of human experience, this collection challenges the divisions of personal and global, indigenous and “everyone else,” all the while celebrating both the humanity and the divinity of the Lady. Playful, erotic and occasionally harrowing, this collection bundles together experimental and inspirational work from a longstanding voice of conscience in Canadian letters. Once again, Arnott carries us into the most intimate terrain, casts her net widely, catches us up.

Synopsis:

Imagine Mercy is a vibrant poetry collection portraying the daily realities of living as an Aboriginal in Canada. David Groulx seamlessly weaves the spiritual with the ordinary and the present with the past. He speaks for the spirit, determination, and courage of Aboriginal people, compelling readers to confront cruel reality with his honest and inspiring vision. The poems in Imagine Mercy portray mixed bloods, resistance, determination, sovereignty, and cultural issues that generate sharply divided opinions and deep emotional struggles. Groulx’s poetic power renders an honest and painful perception of modern-day Aboriginal life with strong voice against prejudice and injustice.

Educator & Series Information

This book is part of the Canadian Aboriginal Voices series.

Additional Information

96 pages | 5.50" x 8.50"

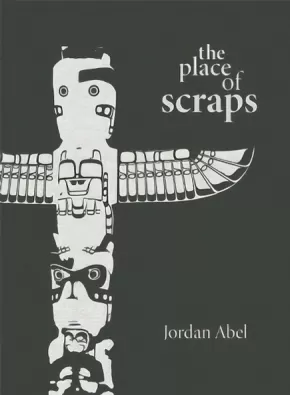

Synopsis:

The Place of Scraps revolves around Marius Barbeau, an early-twentieth-century ethnographer, who studied many of the First Nations cultures in the Pacific Northwest, including Jordan Abel’s ancestral Nisga’a Nation. Unfortunately, Barbeau’s methods of preserving First Nations cultures included purchasing totem poles and potlatch items from struggling communities in order to sell them to museums. While Barbeau strove to protect First Nations cultures from vanishing, he ended up playing an active role in dismantling the very same cultures he tried to save.

Through the use of erasure techniques, Abel carves out new understandings of Barbeau’s writing – each layer reveals a fresh perspective, each word takes on a different connotation, each letter plays a different role, and each punctuation mark rises to the surface in an unexpected way. As Abel writes his way ever deeper into Barbeau’s words, he begins to understand that he is much more connected to Barbeau than he originally suspected.

Synopsis:

One of the first lines of X, Shane Rhodes' sixth book of poetry, is a warning: "this book of verse demands more of verse, this book demands perversity."

In X, Rhodes takes poetry from the comfortable land of the expected to places it has seldom been. Writing through the detritus of Canada's colonization and settlement, Rhodes' writes poems to and with Canada's original documents of finding and keeping. He writes a poem to each of the eleven numbered treaties (the Post Confederation Treaties between many of Canada's First Nations and the Queen of England)--he writes to the fonts he finds in Treaty 5, the river he finds in Treaty 6, and the chemicals he finds in Treaty 8. Rhodes' writes poems to and with the Indian Act.

Beyond the treaties, Rhodes writes formal poetry using Indian status registration forms. He writes to the memory of Oka. He writes to the Government of Canada's Apology for the Indian Residential School System. He writes to the procreating beavers he finds in the Royal Charter of the Hudson Bay Company. X culminates in "White Noise," a long poem grown from Canada's collective rants, threats, cries and shouts in response to the Idle No More protests and the hunger strike of Chief Theresa Spence.

Through out the book, Rhodes surprises with what poetry and art can actually do with the seemingly unsalvageable and un-poetic that surrounds us. The design of X is also exhilarating. Not only is the book reversible--it must be read in two directions--but every page bursts with design, interference and thought.

X sings a new national anthem for Canada, an anthem stripped of patriotic fervor that truly sings of the past many would rather forget and the current state of Indigenous/settler race relations in Canada, an anthem fit for "a land held by therefores, herebys and hereinafters."

Synopsis:

NDN word warrior Marie Annharte Baker's fourth book of poems, Indigena Awry, is her largest and wildest yet. It collects a decade's worth of verse — fifty–nine poems.

Set noticeably in Winnipeg and Vancouver, but in many other places on either side of the Medicine Line as well, the poems are a laser–eyed meander through contested streets filled with racism, classism, and sexism. Shot through with sex and violence and struggle and sadness and trauma, her work is always set to detect and confront the delusions of colonialism and its discontents.

These poems are informed by a sceptical spirituality. They call for justice for NDNs through the Permanent Resistance that goes around in cities. This is bruising and exacting stuff, but Annharte is also one of poetry's best jokers.

In Indigena Awry, you can find fictitious girl gangs coexisting with real boy ones. NDN grannies may be found flirting salaciously in some internet chat room. One might use duct tape to prevent a war. You might be worried that hand–signalling for a Timbit on an airplane flight will be considered a terrorist act.

Annharte may be seam–walking a singular path but she is not without allies. In the United States, they could include Leslie Marmon Silko and Chrystos. In Canada, Beth Brant and Gerry Gilbert. The jazz inflections of Beat writing are often apparent in her work. She swings from a poetic madness into a mad poetics. Way under it all, acting as a deep sort of platform, could be considered the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong'o's project of decolonizing one's mind. Both sketch out an argument that we will not see, feel, or respond correctly in or to our own lives without doing this, because otherwise we will be living within a philosophical myopia generated by a bad fiction.

While Indigena Awry is written for NDN persons, it is highly recommended for truth–seekers of every nature and anarchs of word and spirit. In an Annharte poem you might lose your way only to find what's important.

Synopsis:

Through poems that move between the two languages, McIlwraith explores the beauty of the intersection between nêhiyawêwin, the PlainsCree language, and English, âkayâsîmowin. Written to honour her father's facility in nêhiyawêwin and her mother's beauty and generosity as an inheritor of Cree, Ojibwe, Scottish, and English, kiyâm articulates a powerful yearning for family,history, peace, and love.

Synopsis:

This book is one woman's examination of her role as an otepayemsuak, a Métis, in this 500-year era of resistance and change. We are in a time when many Indigenous prophecies are reaching into the present - those of the ancient Mayan, the Hopi, the Iroquois, the Cree, the Métis. As with the ancient Mayan, where December 12, 2012, marks the end of the long count calendar, according to the prophecy of the Mohawk's seventh generation, we have reached the time to restore Indigenous stewardship of the land. The words that follow the title of the first chapter of the trees are still bending south, are those of Louis Riel: "My people will sleep for one hundred years. When they awake, it will be the artists that give them back their spirit."

Synopsis:

A poetry collection where stories of life’s experiences are distilled into feelings and thoughts that are universal. Reneltta Arluk weaves the traditional and the contemporary together through the eyes of a young Aboriginal woman. Her poems, both sacred and secular, are written with the passions of anger, grief, and love, at once tender and furious. Here are tales of love, betrayal, courage, defeat, acceptance, loss, grief, passion, delight, courting, coming of age, birth and death, youth and old age, hunting and surviving. The poems are united by the history of her ancestors and the ongoing struggle to define what it means to be a tribal member, an Aboriginal, and a woman in the twenty first century.

Educator & Series Information

This book is part of the Canadian Aboriginal Voices series.

Additional Information

|